I’m always impressed by how one book can make a tremendous impact on the world, extending far beyond the writer’s lifetime. This certainly applies to Charles Dickens, born just a year after George, Prince of Wales was appointed Prince Regent. Dickens’ book, A Christmas Carol (originally titled A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas) not only affected the way Victorians celebrated Christmas but is still a major influence on the Christmas values and traditions we cherish today.

Christmas in Jane Austen’s time

If we could travel back in time a couple of hundred years, we’d see that Christmas celebrations before the Victorian era bear little resemblance to how we celebrate today.

In medieval times Christmas celebrations were the highlight of the year, with feasting, pantomimes, dancing, singing, games, gifts, and other fun. However, the Puritans of the 16th and 17th centuries frowned on celebrations in general and forbade any frivolity at Christmas.

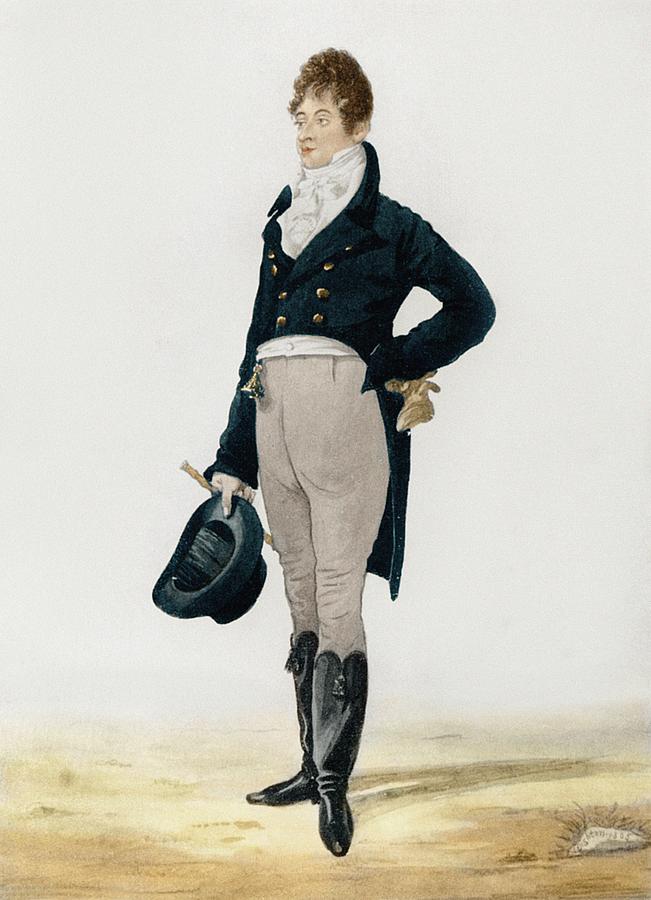

This Puritan influence lingered, and during the 18th century and the Regency era, Christmas was low-key. Games, gifts, and raucous merry making were out. A toned-down observance of the holiday centering on a religious service was in.

In Pride and Prejudice Jane Austen mentions Christmas exactly six times, and the references are brief. For example, Darcy says his sister will stay at Pemberley until Christmas, and Mrs. Bennet’s brother and sister-in-law are mentioned as having come as usual to spend “the Christmas at Longbourn.”

That’s not to say that Christmas wasn’t observed at all. Regency homes were often decorated with greenery such as holly or laurel. People went to church on Christmas Day, and then home to a dinner that could include plum pudding and mince pie.

Lucky servants or tradesmen might get “Christmas Boxes” – small gifts of money – but it wasn’t the custom to lavish gifts on family and friends the way we often do today.

Austen alludes to festivities linked to Christmas during the Regency in Pride and Prejudice through a character in her story, Caroline Bingley.

Caroline, sister of the eligible bachelor Mr. Bingley, sends Jane Bennet a letter, hoping to convince Jane that her brother was no longer interested in her. She writes:

“I sincerely hope your Christmas in Hertfordshire may abound in the gaieties which that season generally brings, and that your beaux will be so numerous as to prevent your feeling the loss of the three of whom we shall deprive you.”

“Gaieties” sounds nice, even if the intent of Caroline’s letter was mean.

Christmas observances in England started to change when Queen Victoria married Prince Albert. Prince Albert usually gets the credit for having the first decorated Christmas tree in England, a Christmas tree being a German custom he brought to his family in the late 1840s. His royal example inspired British families to get their own Christmas trees.

Less well-known is the fact that it was the German wife of King George III, Queen Charlotte, who actually set up the first Christmas tree in England in 1800 in the Royal Lodge at Windsor.

However, Christmas really started to transform into the merry holiday we’re familiar with after a certain novella was published in 1843 and became a smash hit with the British public.

Enter Charles Dickens

On February 7, 1812, while Jane Austen was writing her famous novels and living in a cottage in Chawton, Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth, England.

His childhood was marred by his family’s financial instability. When Dickens was only 12, his father was thrown into debtor’s prison. Young Charles had to leave school and work in a factory for three years. He was able to return to school, and later began his literary career as a journalist, editing a weekly publication for 20 years while writing his stories.

Throughout his life, Dickens authored 15 novels and five novellas, plus nonfiction articles and hundreds of short stories. He often wrote about the plight of the poor and the need to reform living and working conditions.

His literary works include A Tale of Two Cities, Oliver Twist and David Copperfield, all of which were popular during his lifetime and still are. But it’s A Christmas Carol, the little book Dickens had to pay Chapman and Hall to publish because they didn’t think it would sell, that may be Dickens’ greatest legacy.

Adaptations of A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol has been adapted too many times to count, and in every medium imaginable (books, film, cartoons, stage, public readings, television, radio) with new versions appearing every year.

Scrooge himself has been immortalized and re-interpreted by actors in an array of movies, including the critically acclaimed 1951 film with Alastair Sim and the popular Muppet Christmas Carol starring Michael Caine in 1992. Even Bill Murray had a go at the role in 1988 with Scrooged.

The very first film adaptation as far as anyone knows was a 1901 British silent film, titled Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost. The special effects are primitive compared to current cinema, but I’m sure the film was scary for its turn-of-the-century audience. (If you’re curious, you can watch it on YouTube.)

The lasting impact of A Christmas Carol

Scrooge’s transformation from an unloved miser to a beloved philanthropist has helped Christmas evolve into much more than an important religious holiday. It’s also become an occasion to show appreciation for friends and family through joyful celebrations and gifts. Dickens reminded his readers to use Christmas as a time to express gratitude for what they have and give generously to those in need. And, of course, to have fun, too!

~~

This is our last Quizzing Glass post for 2023. We will be here again in the new year.

To borrow Scrooge’s words near the end of A Christmas Carol:

“A merry Christmas to everybody! A happy New Year to all the world.”

~~~

Sources for this post include:

- Inventing Scrooge, by Carlo DeVito, Cedar Mill Press Book Publishers, Kennebunkport, Maine, 2014

- The Man Who Invented Christmas, by Les Standiford, Crown Publishing Group, Inc., New York, New York, 2008

- Eavesdropping on Jane Austen’s England, by Roy and Lesley Adkins, Abacus, an imprint of Little, Brown Book Group, London, England, 2013

- A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens, first published in December 1843, in London, England, by Chapman and Hall.

Images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons